My father gave me most of his tools some years ago when he decided to downscale and pursue other interests. He was very much a powertool woodworker as apposed to a hybrid woodworker (someone who uses both hand tools and power tools) or a handtool woodworker. I never even knew that he was as his way was the only way I knew, until I started reading American woodworking magazines and listening to podcasts such as the one by the Modern Woodworkers Association (my favourite) and Wood Talk (highly recommended). Now I realise that there are other ways to approach woodworking conundrums.

It is not as if I am not grateful for everything I learnt from my Dad, as it certainly got me hooked to woodworking in a big way, but I am finding myself gravitating towards quality handtools with a vengeance. I guess that would make me a hybrid woodworker with fairly basic handtool skills at present.

This is really a roundabout way to get onto the primary purpose of this post, which is the rehabilitation of the two old Bailey handplanes my Dad handed down to me. It is a no. 4 Smoothing Plane and no.5 Jack Plane that really needed serious attention. I never even knew that one should sharpen the plane irons as my father and I never did. Probably, in hind sight, because we never used them. For this reason they never seem to work very well, which did not encourage any further scrutiny.

That was until I watched the DVD on Plane Sharpening by David Charlesworth and using a sharp Lie-Nielsen No.4½ Smoother. It would not be too much of an exaggeration to say that it was an epiphany. A sharp handplane is poetry in motion. It is psychotherapy for a shrink … literally in my case. David also explains very clearly in his DVD what comprises a functional and well tuned (apart from a sharp iron) handplane, which is all very useful to any woodworker, but especially to plane rehabilitators.

Armed with this new knowledge I set about to rehabilitate these family heirlooms. In the first few pictures you can get an idea of the state they were in. It used to be toilsome to slice Parmesan cheese with these planes, to be honest.

First step was to flatten the soles of these planes and it turned out that they were in some serious need of this particular ministration. An added bonus of doing this is that it makes the shiny parts of the plane body smile with a rewarding gleam. I have to warn you that this is hard work that can take time and perseverance from a woodworker. You do not have to get it 100%, but the toe, the area behind the mouth and a reasonably large area towards or at the heel all needs to be in the same plane.

A Magic Marker is very useful to demonstrate the areas that needs attention. Drawing a grid (as shown) before taking a few swipes over wet-and-dry-sandpaper fixed to 10 mm thick float glass, would reveal the troublesome spots in no time. Please note that I left the plane irons clamped in their usual position, only making sure that they are retracted well into the plane body in order not to get damaged by the flattening activity. The reason behind this is that the clamping action of the lever cap deforms the sole ever so slightly which means that you want to flatten it while under tension.

The remnants of gridlines clearly indicate the low lying areas as seen below.

Then it becomes a question of elbow grease, burning some midnight oil or whatever it might be called. Here you can see how I used my sharpening jig to do the flattening. If you want to read the post on how I made this jig find the post called “My version of Deneb’s sharpening jig” under the category “Jigs”. This jig clamps wet-and-dry sandpaper on a piece of float glass by means of two cauls.

The final product is well worth the effort I thought.

Next I took the planes apart completely, including removing the plane irons with their chipbreakers, the frogs, the totes and knobs.

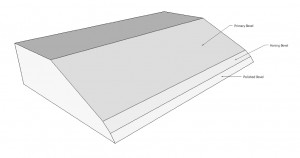

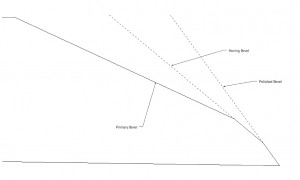

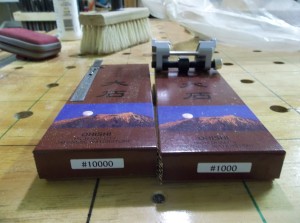

Here you can see how I sharpened the new replacement blades I bought from Lie-Nielsen. If you are interested in purchasing replacement blades for old Stanleys, check out Lie-Nielsen’s website, they have the whole range. Their blades are definitely the business. Their blades are prepared at a primary bevel angle of 25º and ground flat as … oh no just remembered this is a family website … but you really do not have to do too much work on the back at all.

I honed a 33° honing angle on my 1000 grid Ohishi waterstone and polished a 35º final cutting angle on a 10 000 grid Ohishi stone. Both blades were sharpened with a cambered edge.

In the picture below you can see the Nagura stone I use with the 10 000 grid stone.

Here you can see how the totes and knobs looked like prior to rehabilitation. Clearly some type of varnish left that was starting to look seriously weathered. I removed the the varnish with a card scraper before tidying it up with sandpaper.

A last picture before the frogs came off.

The two screws that fix the frog to the body of the plane is evident in the first picture. In the third picture you can see the screw that helps you position the frog during reassembly depending on how tight you want the throat.

Next step was to carefully remove the worst of the rust from the frog’s surface that supports the blade with a fine flat file.

In the first picture below you can see how I then used a magic marker to blacken all the surfaces that is in contact with the back of the blade. In the next picture you can see the setup I used with 150 grid wet-and-dry sandpaper on a piece of float glass on the edge of the table in order to easily hone the most important front section of the frog. In the third picture you can see how the leftover magic marker indicates the areas that needs more attention after just a few strokes on the sandpaper. The last picture show how it is all cleaned up and flat as … yes you know what I mean.

Here you can see how I cleaned up and flattened the areas of the frog that is in contact with the plane body.

Speaking of plane bodies, here you can see how they look prior to a Ballistol treatment.

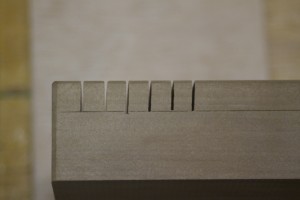

One of the most important parts of this rehabilitation operation is the work done on the chipbreakers. You want to flatten the area in contact with the blade at an angle that will ensure that the absolute tip of the chipbreaker sits flat on the back of the blade. This is accomplished by the setup as shown. You can see how the angle created will ensure that only the tip ends up flat on the blade.

Here you can see how I decreased the angle slightly for honing and polishing. In the last picture you might be able to appreciate the perfectly polished and flat area that will ultimately sit on the back of the blade.

The lever cap being made of cast iron is much easier to flatten, but again remember to set it up so that you only flatten the area that matters at the very tip that will be in contact with the chipbreaker. These lever caps were not even close to flat in the mentioned area.

Here you can see the totes and knobs before and after a Ballistol treatment.

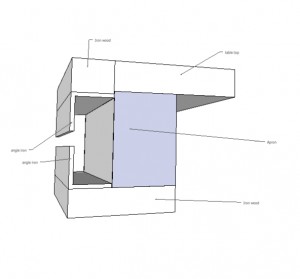

Both totes were very wobbly due to very slack tolerance around the two raised cast iron areas on the base. I decided to remedy this by inserting some Epoxy putty and squeeze the tote into position, in order to create a perfect fit.

Finally all the parts were reassembled with the frogs set up to create a very tight throat on both planes. I can really recommend doing this for those of you who do not mind some elbow grease in return for a pleasing precision tool. There can be no comparison between how these planes cut post rehabilitation compared with prior to it. It is an absolute pleasure.

As per usual, the proof is in the pudding. Here are some of the first shavings I took. It is poetry, I tell you!

I think they are ready for another few hundred years of work.

22/4/2014